THE GHOST RIDER HAD ENJOYED A LONG RUN at his original home, Vin Sullivan's Magazine Enterprises, from late 1949 right through to the spring of 1955, in a variety of titles: Tim Holt (which became Red Mask), Best of the West, Bobby Benson and, of course, his own title The Ghost Rider. Dick Ayers, later to be one of Jack Kirby's most important Marvel inkers during the early 1960s, was the artist on every single episode of the character. So when comics fan Roy Thomas landed a job at Marvel Comics in 1965 as Stan Lee's assistant, he brought with him a broad knowledge of characters from earlier periods of comics, some of which he'd revive over his first few years at Marvel.

|

| Marvel version of The Ghost Rider was pretty much identical to the Magazine Enterprises original, including the artist Dick Ayers. |

The Ghost Rider had been one of Thomas' favourite comics when he was a kid so, figuring that the character had fallen out of copyright, Thomas pitched the idea of a revival to Stan, with Dick Ayers as the artist. It was a bit of a no-brainer.

WHO THE HECK IS ROY THOMAS?

Roy William Thomas Jr was born in Jackson, Missouri on 22 November 1940. An enthusiastic comic fan from his earliest years, Thomas would write and drawn his own strips and circulate them to friends. While studying for his degree at Southeast Missouri State University, he became involved in organised comic fandom through pioneer fanzine publisher Jerry Bails. The burgeoning DC superhero revival of the early 1960s led to Bails' fanzine Alter Ego, which Thomas took over in 1964. During those first years of the 1960s, Thomas had letters published in Green Lantern 1 (Aug 1960), The Flash 116 (Nov 1960), Fantastic Four 5 (Jul 1962), Fantastic Four 15 (Jun 1963) and Fantastic Four 22 (Jan 1964).

|

| Alter Ego, then and now: The first issue appeared in 1961, edited by Jerry Bails with cover art by Roy Thomas. The fanzine went through a few stops and starts, but is still published today. |

In 1965, Roy Thomas was offered a trial position as editorial assistant to DC's Dark Overlord Mort Weisinger. It wasn't a happy experience. Weisinger was notorious for being rude and abrasive and, coming from a background in education, this wasn't what Thomas was expecting. After a day's haranguing from Weisinger, Thomas told The Comics Journal in 1981 that, "I actually remember going to my dingy little room at the George Washington Hotel in Manhattan, during that second week, and actually feeling tears well into my eyes, at the ripe old age of 24. I've never done that over a job, before or since, but Mort really got to me."

That same week, Thomas wrote a letter to Stan Lee at Marvel Comics. "Not applying for a job or anything ... I just said that I admired his work." Stan remembered Thomas from his work on the Alter Ego fanzine and called Roy the next day. "He just asked me - on the phone - if I'd be interested in trying a writers' test Marvel gave." So Thomas went up to the Marvel office and collected the test pages from Flo Steinberg. That evening "I returned to my hotel room and banged out a few pages of dialogue for some Fantastic Four pages - they were from the conclusion of Annual 2, as I recall - and turned them in the next day."

Thomas got a call from Flo asking him if he could stop by the Marvel offices and meet Stan. "The previous day or so, Mort had been in rare form, so I guess I was ripe without knowing it. Ten minutes after I met Stan, he asked me what he had to do to get me away from DC. I was surprised to find myself telling him that all he had to do was offer me the $110 a week Mort had offered me when I was back in Missouri, but which had dropped to $100 a week, mysteriously, when I actually showed up. I also told Stan I'd have to give Mort indefinite notice, since I didn't want to leave him in the lurch. As it turned out, that was beside the point, because the minute I told Mort he ordered me out of the DC offices. I was back at Marvel less than an hour after I first left, and had a Modelling with Millie assignment (44, Dec 1965) to do over the weekend. It was a Friday."

From there, Roy Thomas became a staff writer at Marvel, starting with a few issues of Millie the Model, Modelling with Millie and Patsy and Hedy. "I wasn't hired as an editor or assistant editor." Thomas wrote in Marvel Age of Comics, in 2022. "I was supposed to come in 40 hours a week and write scripts on staff. I sat at this corrugated metal desk with a typewriter in a small office with production manager Sol Brodsky and corresponding secretary Flo Steinberg. Everybody who came up to Marvel wound up there, and the phone was constantly ringing, with conversations going on all around me. Almost at once, even though Stan proofed all the finished stories, he and Sol started having me check the corrections before they went out, and that would break up my concentration still further [and] they kept asking me to do this or that, or questions like in which issue something happened, or Stan would come in to check something, because I knew a lot about Marvel continuity up to that time. It quickly became apparent to them, too, that the staff writer thing wasn't working, and Stan segued me over to being an editorial assistant, which immediately worked out better for all concerned."

Once Stan was confident that Thomas was able to mimic the Marvel style, he moved Thomas up to Sgt Fury, starting with issue 29 (Apr 1966), and X-Men from issue 20 (May 1966).

|

| Thomas would script just a year's worth of issues of Sgt Fury, but he stuck with The X-Men for the rest of the run, and was instrumental in reviving the team as The New X-Men in 1975. |

It wouldn't be long before Thomas started his legendary run scripting The Avengers, starting with issue 35 (Aug 1966), which would last till issue 104 (Oct 1972). During those six years, Thomas added Hercules to the lineup, created The Red Guardian (The Black Widow's husband), introduced a new Black Knight, revived the Golden Age hero The Vision, added the Black Panther to the lineup, and gave us the Kree-Skrull war. Artists that Thomas managed to attract to the title included John Buscema (notably the run between 55 and 62, with sublime inks from George Klein), Barry Smith and Neal Adams.

|

| Though Thomas would work with many super-star artists during his run scripting The Avengers, I still have a real soft-spot for Don Heck's work on the title. |

Back in 1966, Thomas had been scouting around, looking for other writers to bring in to Marvel. His first success was in getting Stan to hire Gary Friedrich. Thomas then went after Denny O'Neill, who had been writing a series on the burgeoning comics industry for a local Missouri newspaper. Roy pretty quickly handed Millie the Model off to Denny and Sgt Fury to Gary. And it was probably about this time that Thomas started pitching the idea of a Ghost Rider revival to Stan.

THE GHOST RIDER HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE

Fast forward ten years and with the co-creator of Ghost Rider, Dick Ayers, safely ensconced at Marvel Comics, Roy Thomas pitched his first revival idea at Stan Lee. The Magazine Enterprises character The Ghost Rider hadn't been maintained as property by ME owner Vin Sullivan and, legally at least, was up for grabs. With a green light from Stan. Roy got together with his own protege Gary Friedrich and concocted a revised version of the classic western hero.

|

| By this point in his career, Dick Ayers had developed into a very slick artist, even if he wore his Kirby influences on his sleeve. Shame about the unsympathetic Vince Colletta inks, though. |

This Ghost Rider starts out as teacher Carter Slade, who's been hired to educate the children of Pitchfork, Missouri. As he approaches the town he witnesses an attack on a homestead by "indians". He does his best to fight them off, managing to reveal them as white men in disguise, but is shot and left for dead by his attackers. However, the homesteaders' young son, Jamie Jacobs, has survived the attack and tries valiantly to get the injured Slade to the town doctor. On the point of collapse, Jamie is discovered by genuine Indians and taken back to their medicine man Flaming Star. Against all odds Slade survives and Flaming Star takes this as a sign that Slade has been spared by the spirits for some greater destiny as "He Who Rides the Night Winds".

And with that, Flaming Star gives Carter Slade a Cloak of Brightest Night, some glowing meteor dust and then guides him to a wild white stallion that Carter must tame for himself. It just remains for Slade to deal with Jason Bartholomew, the illegal sponsor of the "indians" who are trying to drive the homesteaders away.

|

| That's some wordy exposition page right there. I have to wonder how much cutting up of the art board did the Marvel production department have to do to fit in all that verbiage. |

It's an okay origin story, which pretty much follows the debut of the 1950s version, land-grabbing ranch-owner, fake indians and all. It is a bit dialogue heavy, but this is right at the start of Thomas' and Friedrich's writing careers, so they can be cut some slack for that. The inclusion of the kid sidekick indicates to me that Marvel was still chasing the ten-year old audience, and the addition of a love interest in the shape of the lovely Natalie Brooks - coincidentally the sister of the socially hostile Ben Brooks - has Stan Lee's fingerprints all over it.

|

| Ladies and gentlemen, the lovely Natalie Brooks. |

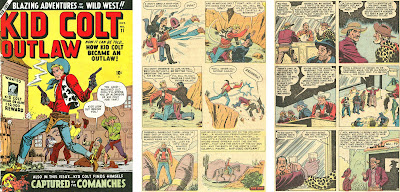

The 17-page Ghost Rider story is topped up with a six-page reprint from Kid Colt Outlaw 105 (Jul 1962), and Stan takes a paragraph on the Bullpen age to plug Ghost Rider and the other three Marvel western titles.

|

| The Bullpen Bulletin page for February 1967, with an illustrated plug for the first issue of Ghost Rider - click image to enlarge. |

It does seem a bit cautious to only invest in 17 pages of new script and art in the debut issue as though Stan, or more likely publisher Martin Goodman, isn't confident the book will sell enough copies. Though the Ghost Rider page count would increase later, the caution wasn't altogether unfounded.

With the second issue, Ghost Rider began to feature costumed or super-powered foes. The story starts with the Ghost Rider running off a gang of cattle rustlers using his customary tactics of pretending to be a headless horseman, making spooky talk ("Begone, servants of evil, lest you taste the vengeance of he who rides the night winds.") then fading into the night. After that skelping, Bart and his gang of rustlers decide it's better to find another territory, where the pickings might be a little easier. As they're packing up, another mysterious figure, The Tarantula, appears and tells them that they are running from a fake ghost. If they join him, he'll finish The Ghost Rider and they can run the entire state.

The next night, The Tarantula and his gang show up in the town of Bison Bend and demand $100 per family for his "protection". Only Natalie's brother Ben stands up to the gang and is knocked down by one of their horses for his trouble. But as The Tarantula and his gang ride off, The Ghost Rider appears and shoots the guns from their hands. And even though The Tarantula uses his whip to bring down a building on top of The Ghost Rider, our hero emerges unscathed. In desperation, The Tarantula grabs Natalie as a hostage, but The Ghost Rider frees her with his near-invisible Lariat of Darkness, making look like the girl is flying from the villain's grasp. With young Jamie projecting an image of The Ghost Rider from the shadows so GR appears to be in two places at once, The Tarantula finally admits defeat and flees.

There were a couple of other interesting details in the issue. We're briefly introduced to Clay Rider, Natalie's fiance. He pops up in one scene and then disappears from the story, leading me to suspect that he may be The Tarantula - or at least that Gary Friedrich wanted us to think he might be. Next, Friedrich lines up Ben Brooks - who we know is deeply sceptical of The Ghost Rider's motives - to be the new sheriff of Bison Bend, which could spell trouble for Carter Slade. And, of course, in the darkness The Tarantula gives The Ghost Rider the slip, teeing him up for a return match.

|

| Calling the villain The Cougar is doubly misleading. For one thing, he's not a costumed villain in the traditional sense and, for another, he's not actually the bad guy ... his brother in law is. |

The Ghost Rider 3 (Jun 1967) gave us a new novelty villain, The Cougar, in reality circus trainer Adano Adriani, who comes complete with a Chico Marx comedy Italian accent. Adriani is a reformed crook now working for Mr Barton the owner of the Barton Brothers Circus, though it's never made clear which Barton Brother he is. When Barton is killed and the box office takings pilfered, Adriani inevitably becomes the prime suspect. But The Ghost Rider doesn't believe the animal trainer to be guilty and breaks him out of jail to try to prove his innocence. It's not really clear why The Ghost Rider needs Adriani out of jail. He could quite as easily investigate the case with Adriani safe from harm in his jail cell. Anyway, Sheriff Ben Brooks believes the Ghost Rider to be involved, despite the compete lack of evidence. The real culprit turns out to be the no-good brother, Philip, of Adriani's adoring wife. Killer unmasked, The Ghost Rider fades into the night, leaving Sheriff Brooks gnashing his teeth and the lovely Natalie wishing her brother would go easier on The Ghost Rider.

We also get to see Natalie's sketchy fiance again in one scene, his name now mysteriously changed from Clay Rider to Clay Riley, though Friedrich doesn't give him anything to do apart from hang around and look smarmy. I sure hoped Gary was going somewhere with this ...

The fourth (Aug 1967) issue of The Ghost Rider featured the return of The Scorpion, actually an old villain who had appeared the previous month in Rawhide Kid 57, but now under a new name, The Stingray.

Bison Bend teacher Carter Slade is hosting a dance to raise money for school textbooks, when The Stingray grabs the takings and flees, pursued by Sheriff Ben Brooks' posse. But instead of chasing the real thief, stubborn Brooks leads his deputies in pursuit of The Ghost Rider instead, letting The Scorpio get away. The next night, while the posse set out in search of the Ghost Rider (again), The Scorpion takes the lovely Natalie Brooks hostage (again). But The Ghost Rider has witnessed the abduction and captures The Stingray, unmasking him as the town druggist, Jim Evans (unnamed here, but I looked it up in Rawhide Kid 57). At that very moment, the Sheriff and his posse show up, forcing The Ghost Rider to flee. Then just as the Sheriff aims at the Ghost Rider's back, The Tarantula shows up and disarms Brooks, claiming to be protecting his "friend", further deepening Brooks' distrust of The Ghost Rider.

|

| He's back ... the man with the fake Spanish accent. This time claiming that he and The Ghost Rider are partners. Just what is his game? Will we ever find out? |

As readers might have suspected, the fifth issue (Sep 1967) of The Ghost Rider features the return of the whip-wielding Tarantula, still claiming to be the partner of GR. In the opening scene, The Tarantula robs the Bison Bend bank and rides off after shouting that he has to go and divide his take with his partner The Ghost Rider. The townsfolk, disappointed that Sheriff Brooks didn't stop the robbery decide to offer a reward for the capture of The Ghost Rider. For some reason this really upsets the lovely Natalie Brooks. Later that night, The Tarantula finally uncovers the location of The Ghost Cave, and ponders that it's only a matter of time before he figures out who The Ghost Rider really is.

Back at Bison Bend, Sheriff Brooks has a surprise visitor - Federal Marshall Lance Sterling, who says he's been sent to help track down The Ghost Rider ... and if you think Brooks is obsessed with catching The Ghost Rider, well you just haven't met Lance Sterling yet. Later that night, The Ghost Rider confronts Sheriff Brooks trying to convince him that they're on the same side. But the conversation is interrupted when The Tarantula sets fire to the town jail. The distraction allows Brook to draw on the Ghost Rider, but the lovely Natalie tries to protect The Ghost Rider and is shot by her own brother.

|

| Though this is a book-length story, I strongly suspect it was drawn first as a 17-pager and Stan just had Dick Ayers add these two pages to extend the story to full-length. |

The showdown between The Tarantula and The Ghost Rider is a bit of a let down. Though The Tarantula defeats The Ghost Rider, he develops sudden amnesia and rides off without unmasking his fallen foe. We don't learn who The Tarantula really is, though some of the things he says indicate that he is a citizen of Bison Bend, and none of them in a Spanish accent.

|

| The sixth issue of The Ghost Rider takes us back to the village where Carter Slade first received his mission from Indian medicine man, Flaming Star. |

The Ghost Rider 6 (Oct 1967) is a bit of a change in direction. Summoned to the Indian village by his benefactor Flaming Star, the Ghost Rider is given a powerful amulet - The Spirit Stone, a piece of the meteor that foretold of his coming - which bestows great strength on the wearer. But as he leaves the village, The Ghost Rider is shot in the back by disgruntled brave, Towering Oak, who covets The Spirit Stone for himself. Towering Oak takes the Stone then, back at the Indian village, confronts Flaming Star and the other braves. Though he claims to be The Stone's rightful owner, Flaming Star tells him that the ownership can only be determined via trial by combat, setting the stage for a showdown.

Meanwhile, Carter Slade is riding to find out how the lovely Natalie Brooks is doing, after being accidentally shot by her brother in the last issue. But he's flagged down by one of the Indian braves with a summons from Flaming Star. Putting his visit to Natalie on hold, he changes to The Ghost Rider and heads for the Indian village and his showdown with Towering Oak. Of course Towering Oak is defeated when The Spirit Stone extracts its toll on his body and kills him mid-battle. The Stone will be interred with Towering Oak's remains, never to be used by mortal man again.

Thankfully, no Vince Colletta inking this issue but, to be fair, George Roussos isn't much of an improvement. I think I preferred this story over the costumed villain tales Gary Friedrich had been pitching us since issue 2. This explores the native American lore behind the Ghost Rider a bit more, even though it's not exactly The Teachings of Don Juan.

The final issue, Ghost Rider 7 (Nov 1967), opens with the lovely Natalie Brooks making the perilous journey to Denver for the operation that might allow her to walk again, accompanied by two of the three men in the world who love her most - her brother Ben and her fiance Clay Rider/Riley. Even now, Ben is a bit twisted out of shape, blaming The Ghost Rider for Natalie's shooting. But, Ben mate ... you pulled the trigger. Take some accountability, for goodness sake.

Shadowing the covered wagon is Carter Slade, aka The Ghost Rider. Like Ben Brooks, he's also a bit confused about who's responsible for Natalie's condition. Suddenly, Slade is set upon by a crazed "Mountain Man", who doesn't care much for intruders, and is taken prisoner. Meanwhile, Ben and Clay decide to take shelter in a nearby cave against the gathering snowstorm. It's not long before Mountain Man arrives to take care of these intruders, too. But when he sees Natalie, he has a meltdown, mistaking her for his long-lost love, Melinda.

There's an unnecessary scene where The Ghost Rider tries to convince Ben to work with him against Mountain Man to save Natalie - it doesn't go well. The Ghost Rider returns to Mountain Man's shack, reveals the crazed hermit's real name - Zebediah Jones - and his back story. The old man's mind had become unhinged when his wife was killed in an Indian massacre years before. Zebediah dies saving Natalie when the roof of his cabin collapses. The Ghost Rider takes over the transporting of Natalie to Denver for her operation.

It's a very odd story, full of forced coincidences and random events that exist only to move the plot forward. The scene where The Ghost Rider tries to convince Ben to put their differences to one side for Natalie's sake seems awfully like padding to fill out the 17-page tale to length.

|

| Not sure what's going on with Herb Trimpe's inking here, but it looks like he did it in the dark with a ballpoint pen. |

The cancellation of the title must have been sudden, because not only does the final panel of the story trail the next adventure, "Hurricane", but there's also no mention that this is the last issue on the letters page, usually one of the last items to be prepared for press.

While I loved the concept (pretty much identical to the original Magazine Enterprises series from the 1950s), I have to admit that the stories and scripting could have been a lot better. Gary Friedrich was very likely directed to pit The Ghost Rider against costumed villains to give the series a superhero slant, but I think that's at odds with the core premise of the character. I think it would have been more effective if at least some of the stories had used fake supernatural menaces, in the same way that the ME original did, so we could enjoy the spectacle of a fake supernatural character exposing other "supernatural" characters as fakes.

But what I didn't know, until I did the research for this blog entry, was that The Ghost Rider did rise from the grave one more time, in the Bronze Age title Western Gunfighters, with the advertised story "Hurricane" appearing in issue 3. Quite why editor Stan Lee decided not to pick up exactly where The Ghost Rider title had left off I couldn't say. Perhaps he thought the resolution of The Tarantula storyline was a bigger pull. Anyhow, the lovely Natalie Brooks is recovering in her hospital bed in Denver while brother Ben and fiance Clay stand anxiously by. A little later, in the shadows outside Natalie's room, lurks Carter Slade, and we're reminded that all three men blame themselves for Natalie's plight. Suddenly - everything seems to happen suddenly in this strip - The Tarantula appears, knocks Carter to the ground and then flees.

"An hour later" The Ghost Rider has tracked The Tarantula down to his hotel room - no explanation is given for how Carter found The Tarantula. There's a five page fight in which The Tarantula is knocked out and The Ghost Rider unmasks him to reveal ... well, we'll have to wait for the next issue to discover the identity of The Ghost Rider's only recurring villain. I mean, I guessed ages ago - did you?

|

| The Great Unmasking is a bit of a damp squib. I'm pretty sure the readers were way ahead of the scripters in this case. Especially if they'd read Amazing Spider-Man 39 (Aug 1966). |

The Ghost Rider story in Western Gunfighters 2 (Oct 1970) picks up a the exact moment where the last episode finished. The Ghost Rider is standing over the unconscious form of Clay Riley, who's just been unmasked as The Tarantula. Suddenly Sheriff Ben Brooks crashes through the door and ... refuses to believe the evidence of his own eyes. His friend Clay could never be a criminal. It must be some sort of frame-up ...

Realising his case is hopeless, The Ghost Rider shoots out the oil lamp in the room (again? He already did that last episode), loads Riley onto a horse and disappears into the night. Once clear of town, The Ghost Rider pauses to reflect on his best course of action. It'll be hard to prove to a Marshall that Riley is really the Tarantula. Momentarily distracted by his pondering The Ghost Rider fails to notice that Riley has recovered and is now springing at him, despite Clay's hands being tied behind his back. A tussle ensues.

Meanwhile back at the hospital, perhaps alerted by some sixth sense, the lovely Natalie Brooks awakes from her coma, calling Clay's name. The doctors confirm that not only is she awake but the operation to restore her ability to walk has been a success. Back at the fight, Clay doesn't fare so well. Knocked off a handy cliff by The Ghost Rider, Clay lands on his head and appears to forget that he is The Tarantula.

Though the artwork by Dick Ayers and Tom Sutton is a big improvement over the Ayers/Colletta combination seen in GR's own book, this scripting is tired, coincidence- driven stuff - Gary Friedrich is capable of much better work than this. It's as though his heart wasn't in it. Perhaps this was a filler mandated by Stan to bring readers up to speed before continuing with the actual next story in the series, "Hurricane", announced at the end of Ghost Rider 7.

|

| Harry Kane the Hurricane, for all his speed, isn't much of a threat to the mighty Ghost Rider. In fact, you could say he's a bit of a pushover ... |

It would have been scheduled for at least 17 pages if it had appeared as originally intended in The Ghost Rider 8, but in this incarnation, it ended up as a 10-pager. Consequently, Gary Friedrich gallops through the plot every bit as quickly as the story's villain Hurricane. Not that there's a great deal of plot to gallop through.

|

| Stan doesn't seem to recall which issue of Two-Gun Kid that The Hurricane originally appeared in ... but we know, don't we, readers? It was issue 70 (Jul 1964). |

While Harry Kane, aka The Hurricane, is trying out his powers in the desert, he's spotted by Carter Slade, who's taking the lovely Natalie Brooks to Denver for her operation (it's a flashback, you see). Kane doesn't want any witnesses to his powers so decides to find out how much Carter knows. There's a bit of pushing and shoving and Kane discovers the Ghost Rider costume hidden in Carter's wagon. No match for Kane's speed, Carter is trussed up with rope and hurled off a handy cliff. Kane then turns his murderous attention on the lovely Natalie Brooks. Just as he's about to shoot the helpless girl, The Ghost Rider appears (isn't his costume still hidden in the wagon?) ... Kane charges at The Ghost Rider at full speed and right over the cliff he'd chucked GR over just moments before.

I'd rather have seen Friedrich spend a little more time on this and perhaps present it as a two-parter. As it stands, The Hurricane has hardly made an appearance before he's despatched by The Ghost Rider, which gives the whole thing the feel of a filler.

|

| The story's padded out with three splash pages, which leaves us just seven pages for actually telling the story. Nice image of The Ghost Rider by Ayers, though. |

Western Gunfighters 4 (Feb 1971) pits The Ghost Rider again another of Marvel's b-western heroes, The Gunhawk. When a low-rent gunman tries to bushwhack The Gunhawk, The Ghost Rider intervenes and sends the ambusher packing. That takes up the first eight pages of the story. The Gunhawk isn't fooled by The Ghost Rider's spook act and announces that he's in the area to claim the bounty on The Ghost Rider's head. The final page shows us the return of Ben Brooks and the now-amnesiac Clay Riley (aka The Tarantula) to the small town of Bison Bend. Fortunately, this is a two-parter, so we should get some more story next time.

|

| With art by a pre-Conan Barry Smith and a script by Steve Parkhouse (better known now as the artist on Resident Alien), Outcast is an intriguing concept that never got a second outing. |

One interesting aside about Western Gunfighters 4 is the inventory story "Outcast" drawn by Barry Smith back in 1968 and scripted by my old friend and collaborator Steve Parkhouse. It's an interesting premise about the nameless protagonist, raised by native Americans after his parents are killed during an Indian raid, searching for his identity.

Marvel made us wait four months for the next instalment in the Ghost Rider/Gunhawk battle. But the Ghost Rider story in Western Gunfighters 5 (Jun 1971) wasn't written by Gary Friedrich. For some reason he left it to Len Wein to resolve the tale. Though it's not unsatisfying for that. The Gunhawk arrives in Bison Bend looking to collect the town's bounty on GR. Even so, Sheriff Ben Brooks doesn't want any gunplay in his town and warns The Gunhawk off the rough stuff. Inevitably, the two antagonists face off in the main street in the middle of the night. But before a shot can be fired, some crooks dynamite the town bank. The Ghost Rider is the first on the scene and exchanges gunfire with the bad guys. The Gunhawk and Sheriff Brooks arrive and join the battle. But after The Ghost Rider saves his life by shooting one of the bad guys, The Gunhawk decides that he'll leave GR be, as he appears to be not such a bad guy after all.

|

| You don't have to be Sherlock Holmes to figure out who's behind all the kidnappings of influential citizens in Bison Bend. Not with a character called Reverend Reaper around. |

Len Wein continues as the script in Western Gunfighters 6 (Sep 1971). The plot is fairly straightforward. Someone is kidnapping the officials of Bison Bend. When they try to abduct Carter Slade, the attempt is foiled by the timely arrival of Carter's big brother Lincoln, now a federal marshal. The only one not kidnapped so far is the town pastor, Reverend Reaper. That name and the fact we've never seen him before should tip you off to who is behind the kidnappings. Lincoln keeps watch on the parson, until he sees him ride off with some rough-looking characters. He follows, reasoning that the kidnappers will lead him to the rest of the captives. Lincoln trails them to an abandoned mine and goes in for a rescue. The Ghost Rider also turns up (though it's not explained how he found the mine) and in the battle, Sheriff Ben Brooks leads the captives to safety while Lincoln and The Ghost Rider polish off the bad guys. With the parson revealed as the mastermind, he kicks away the timbers supporting the mine roof and The Ghost Rider is buried in the cave-in.

|

| Not a dream, not a hoax, not an imaginary story. The Ghost Rider really is dead in this issue. Though there would be more Ghost Riders ... |

In the normal course of things, we'd expect that somehow The Ghost Rider would survive and continue his battle against wrong-doers. But The Ghost Rider tale in Western Gunfighters 7 (Jan 1972) was more of an epilogue than a continuation. What we actually get is the funeral of Carter Slade (yes, he really is dead) and a bit of back story from Jamie Jacobs (I was wondering whatever happened to him).

There would be other versions of The Ghost Rider later, but for this incarnation, that was it. Overall I enjoyed the series, both now and then. Often the execution didn't live up to the concept and in that respect, the series was let down by the writing which swerved between adequate and sub-par. Perhaps if editor Stan Lee had spent a little more time nurturing his apprentice scripters we might have seen a better result.

But coming right at the start of Marvel expansionist phase of the late 1960s, it's likely that Stan just didn't have the time. So we can just file The Ghost Rider under "interesting curiosities" and move on.

Next: The Split Covers of Marvel Comics